Booker T Washington: Freedom, Education, Segregation, and More

Born in a slave shanty in 1856 Franklin County Virginia, by age nine, Booker T. Washington fled with his mother and siblings to Malden, West Virginia after the South’s defeat in the Civil War. In 1872, Washington walked 500 miles to enroll in the all-black Hampton Institute, where he excelled as a student, before studying theology at the Wayland Seminary in Washington, D.C.

After graduating from Wayland, Hampton founder Samuel Chapman was so impressed by Washington’s talents, that he recommended him for the role as principal in the newly-formed Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute in Alabama, which is now known as Tuskegee University, where he would serve until his death.

What did Booker T. Washington Believe in?

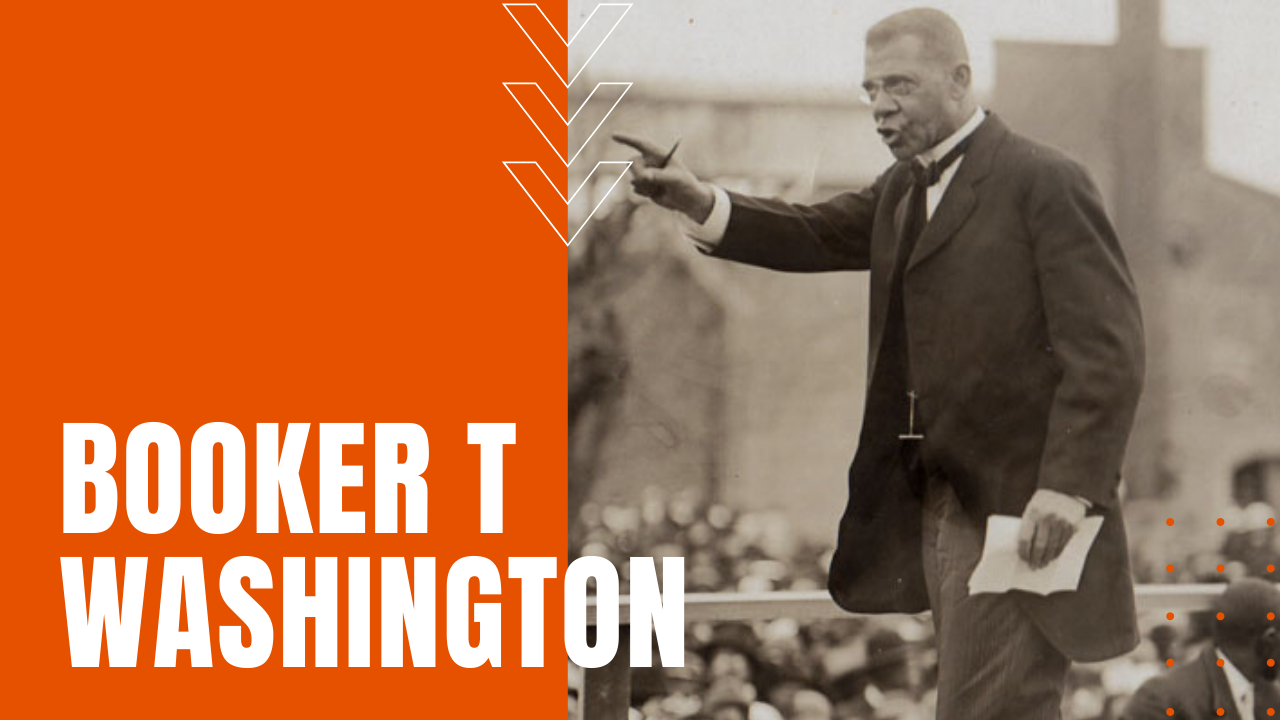

A famed public speaker known for his sense of humor, Washington would go on to write five books, including Up From Slavery in 1901, and in a now-famous September 1895 speech before a majority white audience, he expressed his belief that it was better for black Americans to remain separate from whites, so long as white America granted blacks and women full economic progress, as well as equal access to education and justice through the U.S. courts.

“The wisest of my race understand that the agitation of questions of social equality is the extremest folly,”

Booker T. Washington

he said during his speech, “and that progress in the enjoyment of all the privileges that will come to us must be the result of severe and constant struggle rather than artificial forcing. The opportunity to earn a dollar in a factory just now is worth infinitely more than to spend a dollar in an opera house.”

Criticism from W.E.B. Du Bois

Washington’s speech drew swift criticism from socialist, historian and civil rights activist W.E.B. Du Bois, who slammed what he called Washington’s “Atlanta Compromise” speech in Du Bois’ now famous 1903 book entitled The Souls of Black Folk, while his opposition to Washington’s views on race relations would found the Niagara Movement and the NAACP.

When President Theodore Roosevelt invited Washington to dine with him at the White House in 1901, white Americans—especially white Southern Americans were outraged, yet Roosevelt deemed Washington to be a brilliant advisor on race relations and racial politics in America, which inspired further White House invites by Roosevelt’s successor, President William Howard Taft.

While Washington’s views on segregationists race relations fell out of favor with most Americans, we now know that Washington secretly financed court cases that challenged segregation. He died of congestive heart failure on November 14th, 1915 at the age of 59, having grown the Tuskegee Institute to over 1,500 students, 200 faculty and an endowment of nearly $2 million.