Navajo Treaty of 1868

After years of violent conflicts between the Navajo or Dine People and U.S. forces, including the scorched earth tactics undertaken by Kit Carson, in 1862, U.S. Army General James Henry Carleton ordered all Navajos to be relocated to the Bosque Redondo Reservation near Fort Sumner, in what was then the New Mexico Territory.

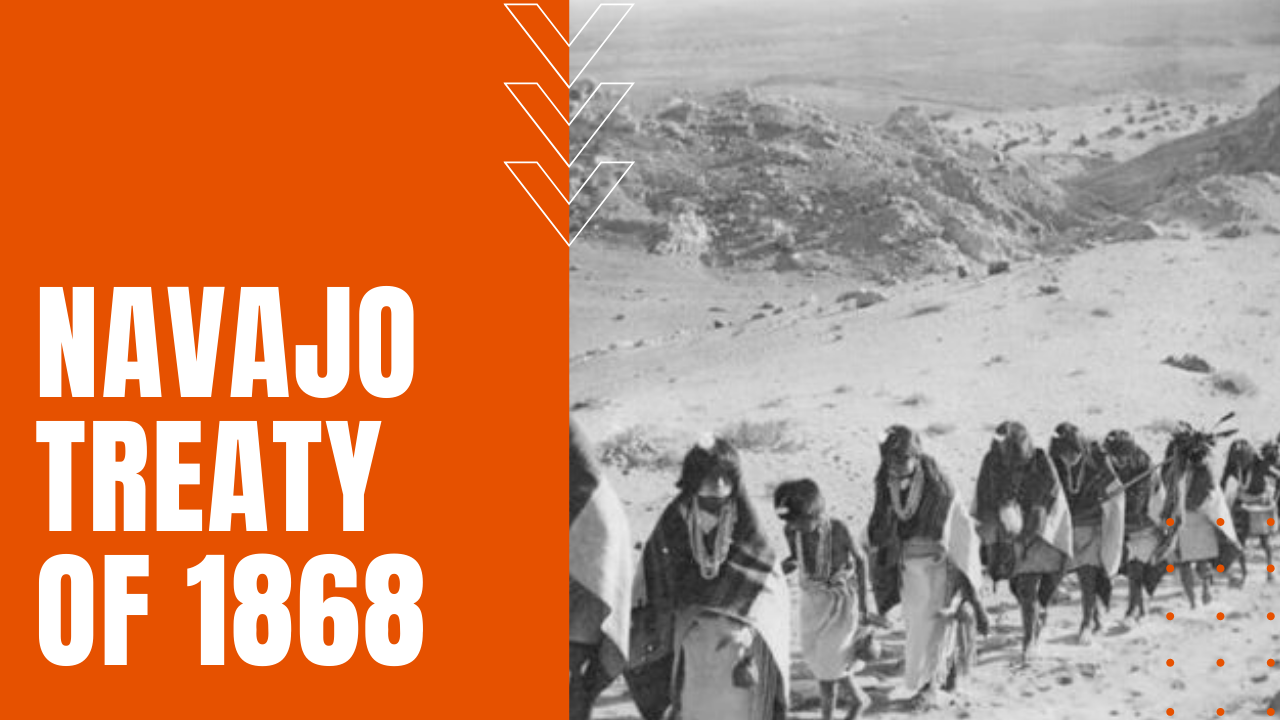

The Long Walk

Carleton’s order would become known to the Navajo as “The Long Walk of 1864,” when some 9,000 to 10,000 Navajo and Apache were forced to march 350 miles from their ancestral home near the Four Corners region, where Carleton’s assimilation plan for the Navajo envisioned that the Dine People would become farmers instructed in Christianity and other basic American practices. Instead, their new home along the Pecos River proved to be remarkably barren for agriculture, leading many Navajo to die from disease and starvation.

After federal subsidies to the Dine People exceeded $2,000,000.00, Congress removed Carleton from command and formed the Indian Peace Commission, where peace commissioners William Tecumseh Sherman and Samuel F. Tappan at first proposed moving the Navajo to the Indian Territory in what is now Oklahoma. Instead, the Dine, led by Barboncito and Manuelito opposed resettlement to the Indian Territory, insisting that they be allowed “only of going home” to their ancestral lands, which centered around Canyon de Chelly in present-day Arizona.

Treaty of 1868: Navajo Sign

In total, 29 Navajo would make their mark on what they called “The Old Paper” or Naal Tsoos Saní in the Navajo, on June 1st, 1868, which was ratified by the senate on June 24th and signed by President Andrew Johnson on August the 12th, allowing the Dine People to return home after four years of deprivation and suffering.

In the treaty, the Navajo agreed to stop all raiding and remain on their homelands in Arizona and New Mexico, while the federal government, in turn, would supply the Navajo with farm equipment, seed for planting and some 20,000 head of livestock. The government also agreed to pay a $10 annual subsidy for 10 years to all Navajo families engaged in “farming or mechanical pursuits,” as well as 10 years of basic supplies intended to help the Dine People regain a strong foothold in their homeland.

The treaty also established formal education for all Dine children aged 6 to 13, while the Dine further agreed not to interfere with any railroad construction through the region. They also agreed that any Dine who committed a crime under federal law would be subject to federal rather than tribal law, making the Navajo Treaty of 1868, a pivotal moment in the Dine Nation’s push for self-governance and freedom.